From Mexico City to Los Angeles: A Professional ‘Crisis’

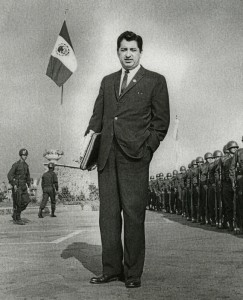

The date that resonates in the minds of many when it comes to slain Los Angeles Times journalist Ruben Salazar is August 29th, 1970: the day he was killed. August 29th bore witness to the Chicano Moratorium, the massive march that marked a peak of the Chicano anti-war movement efforts at that time.

To many people Salazar’s life and legacy has been tenaciously married to this day and to these two events—his death and his connection to the Chicano Movement. Although August 29th, 1970 irrefutably is associated with who Salazar was and his legacy today, to lose sight of the less visible dates in his life would be lose sight of who he was—as not only a journalist and a Chicano, but a person as well.

Salazar began working for the Los Angeles Times in 1959 as a local reporter covering all kinds of stories, including some involving Mexican Americans. In 1965 he was sent first to cover the rebellion-torn Dominican Republic and then to Vietnam, two difficult assignments in very violent places during a highly politically charged time.

In the fall of 1966, Salazar returned closer to home, but remained assigned to the foreign desk as the Times’ Mexico City Bureau Chief. He was living and working in Mexico City in June 1968, when he received a letter from the Times foreign editor Bob Gibson, calling him back to work in Los Angeles. Managing editor Frank Haven was cc’d on the original letter.

“Because of all the new Mexican-American uproar here at home, and muchly heightened interest in these stories, which now are mainly urban, it has been decided that you can contribute more importantly in this area than from Mexico City,” Gibson wrote on June 13th, 1968.

Gibson explained that the decision was out of his hands, presumably implying that it had been made by either the editor in chief at the time, Nick Williams, or the publisher, Otis Chandler. “For some time I have been studying with no decision the possibility of extending you in Mexico, but now I find the matter has been taken out of my hands by a higher level and I have no choice,” he wrote.

Frank Sotomayor, a former Times editor who worked on the foreign desk in the 1970’s, said that Chandler led the transformation of the Los Angeles Times from a mediocre paper known more for its reporting into a respected paper renowned for excellent writing.

“It was a very weak, Republican-partisan newspaper up until the time that Chandler took over,” Sotomayor said. “He wanted to, in a very quick time, make it a world-class newspaper. He decided that one of the distinguishing characteristics of the new L.A. Times was going to be fine writing.”

This larger transformation at the Times may have explained Gibson’s critique, in the letter correspondence, of the editing Gibson said was required on stories filed by Salazar from Mexico.

“As you may have judged from the frequency and thoroughness of rewriting done on your copy, we have been expending an improportionate amount of time getting your copy ready for publication,” Gibson wrote. “This naturally must weigh very heavily in a decision to renew a correspondent’s tour abroad, and it is very likely, therefore, that I would have sought a replacement for you in any event.”

Sotomayor explained that some other foreign correspondents, often working under difficult deadline and filing situations, likely received similar letters during this time. While based in Mexico City Salazar filed stories of political turmoil, terrorism, riots, and social conditions from trouble spots across Latin America and the Caribbean, including Cuba, Panama, Haiti, Honduras, El Salvador, Puerto Rico and Guatemala.

“That was an era long before computers,” Sotomayor said. “Correspondents banged out their stories on typewriters or sometimes scratched notes in their notebooks and phoned in their articles. In some cases, rewriting or heavy editing was required. So (Salazar’s) not an anomaly,” said Sotomayor, who for 11 years edited news reports from around the world while on the foreign desk.

Salazar took Gibson’s critical assessment personally and was less than enthusiastic about this change of location and career path.

He responded to managing editor Haven and cc’d Gibson on June 29th in a nine-page letter, three pages of which catalogued every story he had filed while in Mexico City. Each story was paired with its headline, date of publication, and an asterisk to indicate if it had been rewritten or not. Gibson himself sent out a memo to all correspondents on May 1st, prompting them to do just this.

“As Bob [Gibson] put it in his letter of June 13 my being called back home after a two-year tour is certainly a ‘wrench’ for me,” Salazar wrote on June 29th.

For Salazar, what was most wrenching seemed to be the Times’ accusation of a rewriting problem.

“But it never occurred to me, because I was never told, that I wasn’t doing my job,” he wrote. “How long is it going to take for me to prove myself on The Times?” Salazar’s letter goes on to detail the background, filing processes, dates and various specifics for the 129 stories he filed since he took over the Mexico City bureau.

“Since I took over the bureau I have written 117 stories which appeared in The Times without rewriting and 42 which were edited and rewritten, though the last in the minority,” Salazar wrote. His meticulous professional defense speaks to his confidence in his journalistic work there and an eagerness to continue working for the foreign desk, rather than the city desk.

There may have been an unspoken professional fear, too, of the editors typecasting him as a Mexican-American journalist who should report on Mexican-American issues back in Los Angeles. During this era, the gap between the L.A. Times’ newsrooms and the city’s ethnic reality was huge. When Salazar became a foreign correspondent in 1965 no other Latino Times reporter was hired or assigned to cover the Chicano Movement activism and militancy that grew while he was overseas.

With the March 1968 East L.A. high school walkouts led by teacher Sal Castro and growing anti-war movement within the Mexican-American population, the editors at the Times were caught off-guard and short on Latino talent. Again, most likely as part of the larger efforts to improve the quality of the Times as Chicanos became a more newsworthy beat, they eventually turned to Salazar as the natural reporter to cover this beat.

“I think that would have upset him—that because he was a certain ethnicity and because he had the Spanish fluency, that he would be called back,” said Sotomayor. “He really didn’t understand—because hardly anyone understood—what the Chicano Movement was at that point.”

Gibson’s nondescript summing up of the movement as “the new Mexican-American uproar,” in his letter underscores that idea.

At the time Salazar was called back to Los Angeles, the Chicano movement was mainly known for protest, confrontation, and controversial revolutionary fervor. Sotomayor surmises that Salazar himself was initially doubtful about the news value of the Chicano story in comparison to the news he was covering in Mexico.

A newsroom hierarchy for reporters moves from the bottom up: from local to national to international. Salazar probably saw the move from a foreign bureau chief at such a charged time—the 1968 Mexico City Olympics—to the local desk reporting an unknown “uproar” as a journalistic step back to what he had already covered.

Although he was going through what he described in the June 29th letter to Haven as “the most important crisis in my career at The Times,” Salazar accepted the return to Los Angeles and closed the letter by reinforcing that “my loyalty to The Times remains undiminished. Thanks for taking the time to listen to my side.”

Rosalio Muñoz, as a Chicano anti-war activist, was interested in Salazar at the time in terms of increasing coverage and visibility of a still-growing movement. Yet he also understands Salazar’s more personal reluctance to return to L.A.

“I think another factor you have to consider is that he had settled his family in Mexico City. He had started a family, he had little kids, he was a family oriented guy,” Muñoz said.

Not to mention, Salazar’s family was well cared for in Mexico City, which was common for correspondents abroad. “We lived in a big, big house that had its own gates. We had maids. We went to a private school,” said Salazar’s daughter Lisa. “I just remember my parents being so happy there.”

It is not until the end of Salazar’s June 29th letter that a glimpse of any personal distress about leaving Mexico City emerges. “I only have two months to not only finish much important work her but to start thinking of such mundane but rattling problems as to where to live in Los Angeles and what schools to choose for my children,” he wrote.

Within the image of Salazar as the martyr-like Chicano journalist, it’s easy to assume that Salazar was eager to return to Los Angeles to cover the Chicano Movement.

Within the larger image of his legacy, it’s also easy to assume that his actual reluctance to do so indicated a lack of commitment or real passion for the Chicano issues that he reported on in his last years in Los Angeles.

Both are false assumptions. Salazar’s foreign and war coverage experiences were such that he probably would have been reluctant to leave Mexico City for any reason. However, they shaped a man and a journalist who was committed to reporting any newsworthy story.

“This whole thing – that he wasn’t really committed to the Chicano Movement, that he wasn’t this, that or the other –I think it’s ridiculous. His values were for social justice, and they were broader than just the Chicano Movement,” Muñoz said.

[…] were: Elaine Baran, Melissa Caskey, Juan Espinoza, Regina Graham, Gustavo Gutierrez, Grace Jang, Elena Kadvany, Bianca Ojeda and Frances […]

[…] Each student also chose a story to write from the archives they looked at. I had read some letter correspondence between Salazar and his editors at the L.A. Times from the year he was called back from his position in Mexico as Mexico City Bureau Chief to report on the Chicano unrest in Los Angeles. Contrary to popular belief, he was less than happy about what he saw as a professional demotion, from the international to city desk. Read my story here: From Mexico City to Los Angeles: A Professional ‘Crisis’ […]