Ruben Salazar’s Road To Citizenship

Ruben Salazar, like many Mexicans who immigrate to the United States, dedicated himself to seeking American citizenship as a young man, only to experience a lengthy, difficult process strewn with bureaucratic red tape.

Salazar's declaration of intention sent on Oct. 15, 1947 (Courtesy of Steve Weingarten) Click image to enlarge

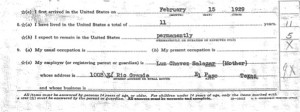

Salazar began the process on Oct. 15, 1947, when he submitted an application for a certificate of arrival and preliminary form for a declaration of intention of citizenship. A photo of Salazar, 19 years old at the time, is attached. At this point in time, Salazar was attending college at Texas Western College in El Paso, TX, where he had been living since he was brought to the United States by his parents as an 11-month old baby. Similar to many Mexican immigrants who are brought to the United States at a young age, Salazar had spent the majority of his life thus far — 18 years — living and feeling like an American. But legally, he was not.

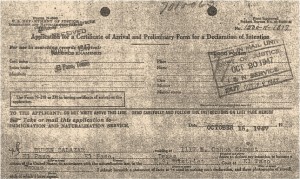

The next day, Salazar was sent a letter from G.C. Wilmoth, District Director at the El Paso Immigration and Naturalization Service. Wilmoth writes that Salazar’s application to file a declaration of intention to become a citizen of the United States has been acknowledged but reminds him that he is not eligible to file a petition for naturalization until his declaration of intention has been on file for at least two years and he has lived for at least five years in the United States. After the two years pass, he will be given a test as to his “knowledge and understanding of the fundamental principles of the Constitution of the United States and of the principal facts concerning the development of this country as a republic.” Wilmoth suggests that Salazar — a college student who has lived in the United States for 19 years — enroll in citizenship classes to prepare.

In December of 1947 and January of 1948, he is requested to come to the El Paso courthouse in connection with his application. The next remaining document jumps to

June 6, 1949, when Salazar politely writes to the Immigration and Naturalization service office to clear an obstacle in his path. In order to register at Texas Western, Salazar had given the university his Declaration of Intention and later claims he believes they lost it.

“I think I am now eligible to apply for my second papers for naturalization,” Salazar writes. “However I can not find my Declaration of Intention. I do have a letter which bears the file number 1500-K-1817 which might help you in finding a record of my Declaration. I would appreciate it very much if you would inform me what steps I can take in applying for my second papers.”

Letter sent from the INS to Salazar on June 9, 1949 (Courtesy of Steve Weingarten) Click image to enlarge

On June 9th, he is again requested to come to the El Paso courthouse. The request letter had handwritten notes on it saying, “Came in and was advised to search diligently for d/I and if not found by Nov. 1949 come in and make application for copy of dec.”

In October 1949, a year after Salazar first began the naturalization process, G.C. Wilmoth writes a letter informing him that as he filed his declaration of intention to become a citizen almost two years previously and has lived in the United States for more than five years, he is now eligible to make an application to file a petition for naturalization.

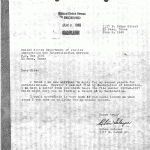

And Salazar, after joining the U.S. Army in October of 1950, has to continue the process from abroad. In October of 1951, Salazar wrote from Friedberg, Germany to the Naturalization Office in El Paso. He explained that a year previously, upon his entry to the Army, he had been told that his naturalization would now be an automatic process.

“At reception center at For Hill, Oklahoma 1950 I was told that as I was now in the Army it would be an automatic process. But since then I have been unable to obtain any definite information on the subject,” he wrote. “As I am anxious to become an American Citizen, I would appreciate it if you could give me the correct information as to what steps I should take to become naturalized.”

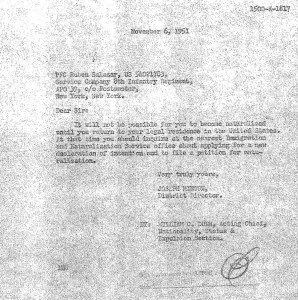

The new district director, Joseph Minton, sent a response on Nov. 6 telling him he could not become a citizen while stationed in Germany.

Letter from the INS telling Ruben he cannot continue the naturalization process while overseas (Courtesy of Steve Weingarten)

“It will not be possible for you to become naturalized until you return to your legal

residence in the United States,” Minton writes. “At that time you should inquire at

the nearest Immigration and Naturalization Service office about applying for a new

declaration of intention and to file a petition for naturalization.”

Two months after his return to the United States, October 1952, Salazar diligently fills

out and submits a form, “A new naturalization paper in lieu of one lost, mutilated, or

destroyed,” repeating pieces of information that he has already provided multiple times.

A month later, on Nov. 26, 1952, a memorandum is sent from the acting district

adjudications officer in El Paso confirming that there are files indicating Salazar filed

Declaration of Intention in 1947. A copy of the declaration is enclosed.

The next remaining document jumps forward about a year to Salazar’s application to file petition for naturalization, stamped with the date of Sept. 11, 1953. On Sept. 16, he was sent a letter from District Director Minton. The letter is identical to the one former Director Wilmoth wrote in October 1947 acknowledging Salazar’s initial application for naturalization and suggesting he — someone who not only attended an American college, but served in the U.S. army — attend citizenship classes.

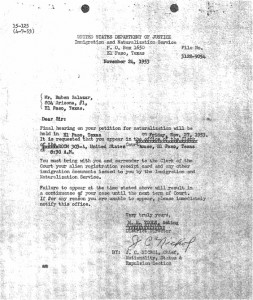

A letter from the INS to Ruben asking him to appear in court for his naturalization hearing (Courtesy of Steve Weingarten)

On Oct. 6, 1953, Salazar was again sent a letter from Director Minton, who requests he appear in the El Paso courthouse on Oct. 13 to file his petition for naturalization. He is instructed to bring his alien registration card, any immigration documents and two U.S. citizen witnesses “who have known you and have seen you frequently since your residence in El Paso began.” He is also instructed to come prepared for an exam in reading and writing English as well as on the U.S. Constitution and government. Ernesto

Hijar and Enrique Roldan appear as Salazar’s witnesses.

On Nov. 24, 1953, a letter is sent informing Salzar that a final hearing for his

naturalization petition will be held on Nov. 27.

Multiple times throughout this six-year-long application process, Salazar fills out forms detailing himself and his path to the United States. He was determined to become a citizen and patiently responded to multiple requests for the same info. He provides a certification of his military service, his immigration registration card, photographs of himself, detailed timelines of his life in the United States. Yet due to circumstance and bureaucracy, he did not become a citizen for many years.

Salazar’s path to citizenship is far from unique; many immigrants today experience the

same lengthy, difficult, bureaucratic process. But as a man who formed an integral part of

The Los Angeles Times, an American establishment, and a man who found great success

in the United States, it is a lesser-known part of Salazar’s history that merits telling.

Jennifer Kobzik also contributed to the reporting of this story.