Letters to the Editor Reveal Readers Had Different Opinions of Salazar’s Stories

“Congratulations,” Paul Bullock of the Institute of Industrial Relations at UCLA wrote in 1964 to the Los Angeles Times. “The publication of Mr. Salazar’s articles represents a long delayed recognition of the importance of the Mexican-American population and of the desirability of giving a voice to the needs and demands of many different ethnic groups.”

Letter to the editor from Paul Bullock published March 26, 1964 (Courtesy of USC Libraries) Click photo to enlarge

As Bullock’s letter to the editor illustrates, some readers held Los Angeles Times journalist Ruben Salazar’s career with reverence. However, public opinions of him also included feelings of criticism and anger, sometimes from the community he wrote about. As one of the first journalists to bring the Mexican American community to the forefront at a time when racial news focused almost entirely on Black and White issues, Salazar was a controversial figure.

Readers of all opinions and backgrounds were vocal throughout his career and they wrote letters to the newspaper to express themselves. The Los Angeles Times published over 50 letters to the editor from 1962 to 1970, both praiseworthy and dismissive of Salazar, revealing the divisive nature of his work.

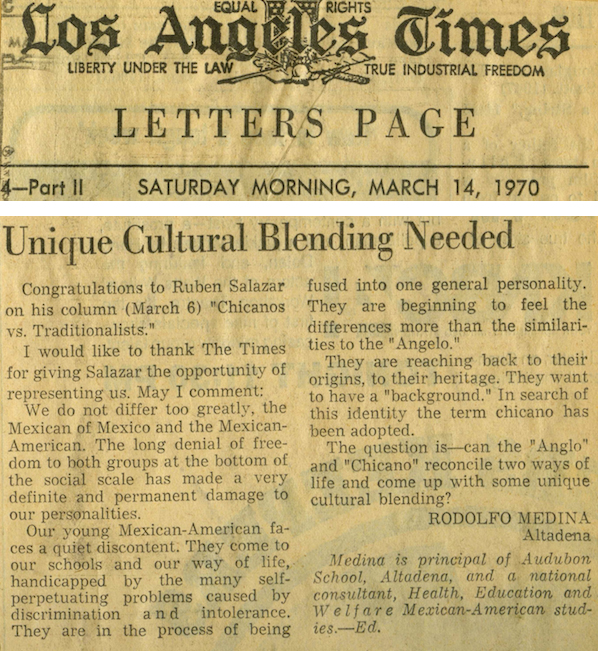

The love hate relationship people had with him was shown in the letters. While some readers would write in saying things like, “I would like to thank The Time for giving Salazar the opportunity of representing us,” others called Salazar “dangerous.” One reader wrote in saying, “[his statement is] dangerous and divisive, beneficial only to bigots who would like to see both racial groups held down in ‘their place’”

From 1959 to 1970 Salazar worked as a news reporter, bureau chief, and columnist for the Los Angeles Times covering a range of issues from the Vietnam War to the 1965 United States occupation of the Dominican Republic. But in 1969, the focus of his work shifted, and he returned to Los Angeles to write about the Mexican American community during the Chicano movement. This was a first for everyone in Los Angeles, including Salazar.

Frank Sotomayor, former assistant city editor at the Los Angeles Times who joined after Salazar left in 1970, said that Salazar was in a very difficult position during this turbulent time.

“He was placed in a position of reporting on a new subject,” Sotomayor said. “He came from a very conservative middle class background so he didn’t really understand the activism that was going on among Chicanos in the early ‘60s.”

Sotomayor said that when Salazar was first covering the Mexican American community, he reported on it like any objective journalist would. However as he became a columnist in 1970, Salazar’s initial role as a reporter eventually changed into his becoming a journalistic advocate for the Latino community.

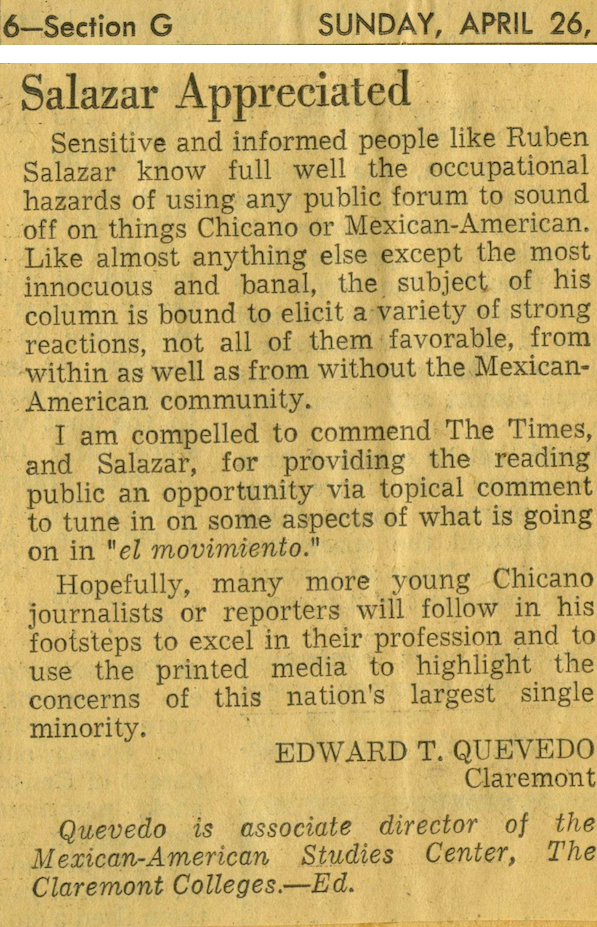

In 1970, the Times published a letter to the editor from Edward T. Quevedo, the associate director of the Mexican-American Studies Center at The Claremont Colleges. His letter commended Salazar’s reporting on Mexican Americans despite the potential “occupational hazards.”

“I am compelled to commend the Times and Salazar, for providing the reading public an opportunity via topical comment to tune in on some aspects

of what is going on in ‘el movimiento,’” Quevedo wrote. “Hopefully, many more Chicano journalists or reporters will follow in his footsteps to excel in their profession and to use the printed media to highlight the concerns of this nation’s largest single minority.”

With both time and more exposure to the Chicano movement, Salazar was able to understand his own sentiments toward the Mexican American community, according to Sotomayor.

“I believe that as time went on and he kind of examined what was going on that he became more personally favorable toward their view,” Sotomayor said. “Then he was able to reflect that in the columns when he was able to express his own opinions.”

In 1964, Eugene A. Kreyche, principal of the El Rancho Adult School, wrote to the editor of The Los Angeles Times, praising Salazar on a series of articles about education in California for Mexican Americans.

“Salazar’s efforts have been exemplar,” He wrote. “I…have found the analysis to be quite enlightening as well as perceptive. I appreciate the candidness in discussing the entire problem and feel sure that the discussion will add considerable information to a rather confused area.”

Until the late 1960s, the presence of Mexican Americans in the Anglo-centered mainstream media like the Los Angeles Times was minimal. Not only was Salazar’s work pioneering in its acknowledgment of Latinos, but as Quevedo alluded to in his letter to the editor, Salazar helped to both lay a foundation for future Latino journalists and for the continued visibility of the Mexican American community.

In June 1970, two months before Salazar’s death, Joe Ortega, Chief Counsel at the regional office of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund, MALDEF, wrote to the Times. His letter highlights the power that journalists hold when they use their medium as the voice for their communities.

“One of the most effective ways of correcting social problems is by a courageous and honest newspaper,” He wrote. “When The Times started the column by Ruben Salazar on the Mexican-American, we felt that it provided an invaluable service to our community in that such a column might help correct some of the problems of our people.”

However, such letters of approval do not represent how the entire Mexican-American community felt about Salazar.

“There was kind of a split in families in terms of generations. It wasn’t necessarily that they thought that Ruben was off; they just didn’t like as they would say, ‘what these young Chicanos were doing, these Chicano militants, these troublemakers,’” Sotomayor said. “They transferred their upset to Ruben and felt that he was giving the young Chicano activists too much attention.”

While younger Mexican Americans saw the term as a “badge of honor,” Sotomayor added that some parents wouldn’t even let their children use the word “Chicano.”

In this vein, Carmen Terrazas, a teacher in Los Angeles, wrote to the editor of the Los Angeles Times in 1969 expressing her upset regarding articles Salazar wrote about education in California.

“As a teacher of Mexican descent, I am incensed over Ruben Salazar’s article…this article is a shocking example of bias and dangerous reporting,” Terrazas wrote. “Finally, I suggest that Salazar research the racist term ‘Chicano.’ He insists on using derogatory terminology in referring to Americans of Mexican Descent.”

At the time, A.S Doc Young was a sports journalist at the Los Angeles Sentinel and one of the first African American publicists to work in Hollywood. Aside from his sports writing, Young was a journalistic advocate for the black community—much like Salazar was for the Mexican American community. In 1970, The Los Angeles Times published his letter to the editor.

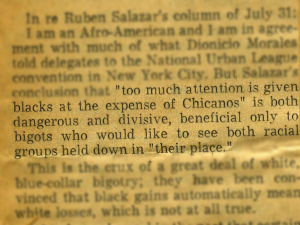

Highlighted excerpt from A.S. Doc Young’s letter to the editor on Aug. 6, 1970 (Courtesy of USC Libraries)

“I am an Afro-American…but Salazar’s conclusion that ‘too much attention is given [to] blacks at the expense of Chicanos’ is both dangerous and divisive, beneficial only to bigots who would like to see both racial groups held down in ‘their place,’” Young wrote. “I fail to see how the election of 1,586 black officials has in any way ‘taken away from’ Chicanos. It would seem that Chicanos could perhaps learn lessons from some of the blacks—and, by that, I do not mean rioting.”

Professor Clint Wilson, Emeritus Professor of Journalism, Mass Communication and Media Studies at Howard University, lived in Los Angeles in the ‘60s, was one of Young’s good friends and wrote a sports column for the Sentinel. Wilson said that Salazar never gave him the impression that his work for Chicanos was work against Black Angelenos.

“If I think about the cadre of leaders in both communities, as well as Asian communities, I think there was an understanding that everybody was sort of in the same boat and basically had the same problems,” Wilson said. “We worked on them together. We realized that to attain the goals that this country was founded upon, it requires inclusiveness.“

On March 13, 1970, just five months before he was killed, Salazar wrote an article, “Latin Newsmen, Police Chief Eat…but Fail to Meet,” about a meeting between Police Chief Ed Davis and a group of Latino newsmen. The journalists wanted to discuss ways to alleviate the growing tension between the Spanish-language press and the police department.

However, after a subtle threat inferred the journalists might have to take action in Washington or at Latin embassies “to get what they needed”, Davis said only he was in charge of the police department and added that he recently wrote to the President telling him off, according to Salazar’s article.

“Telling the President off could not be done in Mexico, the chief told the Latin newsmen, because Mexico had a ‘Napoleonic” style of justice which to Americans smacked of ‘tyranny and dictatorship,’” Salazar wrote in his column.

Four days later on March 17, 1970, Police Chief Davis wrote to the Los Angeles Times demanding a retraction of the article stating that he had been misquoted.

“This is an absolutely lie, “ Davis wrote. “I made no such statement.”

As a footnote to the letter, Salazar cites three other witnesses present at the meeting who agreed that he was accurate. The letter ends with, “Salazar stands by his column.”

On August 29, 1970, just five months later, a Los Angeles sheriff deputy shot and killed Salazar after he had allegedly gone into a bar to escape the chaos of a Vietnam War protest. His controversial death gained national notoriety and had many people pointing fingers at the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, however nothing was confirmed.

While the cause of Salazar’s death may always remain a mystery and whether or not people agreed over the content of his work, Salazar still encouraged dialogue. He broke many of the barriers that existed for Latinos in the media and in creating a more visible presence for them in society.

“It was kind of ground breaking material that had not been done before and people were starved for that type of information,” Sotomayor said. “There was no Facebook, Twitter, or that type of thing so letters were the kind of vehicle that people used to express their points of view. [The letters] validated that what he was doing was a good thing.”