Salazar’s Beginnings As A College Student Journalist

Ruben Salazar’s long career as a journalist is well known, but before he made his name as a professional he started out writing columns for his college newspaper.

What is less known about Salazar is where the Los Angeles Times columnist, KMEX news director, and journalistic advocate for the Latino community first began. Archived documents from Salazar’s time spent at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) reveal that his journalistic endeavors began as a freshman in college.

Salazar was born in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico on March 3, 1928, but soon after immigrated to El Paso, Texas with his family. After he attended high school at El Paso High School, he began college at UTEP, then named Texas Western College, for two years from 1946-1948. For reasons unknown, Salazar left school after his sophomore year, worked for his father for two years then enlisted in the U.S Army in 1950. After completing his military service in 1952, Salazar returned to UTEP to earn his bachelor’s degree in journalism.

As 18-year-old Salazar was experiencing his first two years of college, his writing style—like any aspiring student journalist—was developing and evolving. However, throughout his career, he always wanted to spark public dialogue, break down controversial issues and encourage politically stimulating conversation.

During his first year at UTEP, in 1946, Salazar worked as a reporter for the school newspaper, The Prospector. His articles didn’t have the same controversial nature as they did later in his career; rather they were more so his own observations about happenings around school.

Salazar wrote about a myriad of different topics his first year, ranging from the success of the school’s English department to the need for a Student Union Building. However, no matter the topic, there was one commonality in his writing: he often inserted himself in his articles.

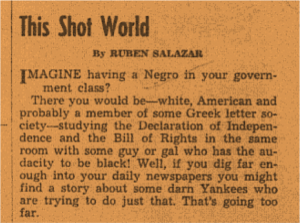

Excerpt from "Interviewing Newspaper Men is a Tough Job" (Courtesy of UTEP Library) Click photo to enlarge

Published on April 25, 1947, “Interviewing Newspaper Men is a Tough Job,” Salazar refers to himself as “this reporter” and “he” throughout the piece.

“That’s what this reporter found out when he tried to interview the city editors of the Times and Herald-Post,” he wrote. “Thinking that the job was a cinch—since he thought newspaper men understood each other—he went to the Times city editor.”

While the development of his voice as an observer and commentator was only in its beginning stages, it was constantly evolving with each article. His sophomore year, Salazar was promoted to News Editor of the paper and began a column titled “This Shot World.” His articles were political and opinionated satires that predominantly emphasized the need for higher education and equality.

In Salazar’s first column published on October 18, 1947, he openly expresses his opinion about the lack of honesty in college sports.

“That football players are bought and paid by institutions of higher learning is of course of secondary importance,” Salazar wrote. “College football is a sport and players play it for sheer enjoyment.”

Even his dedication to objective and quality journalism first appeared in a humorous column on November 22, 1947. He writes about the resignation of the not-well-known yellow journalist, Judy “Pete” Peterson, whom he obviously wasn’t fond of, as the editor of a publication he called, “the much read piece of tripe-Muck.”

“Oh, how much will be missed. ‘Pete’s’ giggles of delight when she has succeeded in twisting a phrase that will make coffee clubs gasp with awe,” Salazar wrote. “Little ‘Pete’ who has done so much to uphold the principals of yellow journalism has at least been gagged.”

Salazar continued writing for The Prospector until he left school and went to work as a jewelry salesman in 1948. Upon his return to UTEP four years later, Salazar re-joined the paper, where he then became the Managing Editor and resumed writing “This Shot World.” However, the focus of Salazar’s columns changed from what was one typical college student’s anti-establishment frustration to a more sophisticated, observant and direct commentary on war, love, race, education, class and equality. Yet, his humor and satirical writing style remained.

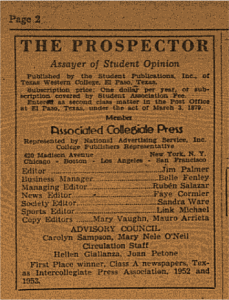

The focus of Salazar’s articles became geared toward marginalized and racial groups. In a December 12, 1953 column, Salazar addressed the issue of race and educational inequality in a satirical column about segregation. He raised the issue at a time when blacks were not allowed to attend the same schools as whites.

“Imagine having a Negro in your government class?” he wrote. “There you would be–white, American and probably a member of some Greek letter society—studying the Declaration of Independence with some guy or gal who has the audacity to be black!”

“To actually have black Negroes in Kelly Hall, right there with us, studying the Bill of Rights—that’s un-American! We’re a democracy and all that sort of thing; but really, let’s not go out of our Southern heads—and take it literally.”

On May 8, 1954, Salazar discusses the flaws of society’s growing apathy toward a quality and well-rounded college education.

“Our colleges are becoming vocational schools. The trade: safe conformity,” he wrote. “College kids cannot afford to have insolent and free minds anymore. For college is the place to make ‘contacts’ which mean jobs afterwards.”

Salazar’s work came full-circle when he began writing columns for the Los Angeles Times in 1970. From the beginning of his career to the end in 1970, Salazar’s work was always infused with an emphasis on marginalized groups and education. He never failed to state his opinions boldly and his ability to spark public dialogue was part of his mission, as made evident in his last column of “This Shot World” on May 8, 1954.

“After this issue This Shot World shuts up its loud mouth for good. To those persons who were kind enough to say they liked the column, thanks,” Salazar’s last column reads. “For those whom this column angered, thanks too. This Shot World intended to anger you. Your cooperation was appreciated.”

UTEP journalism student Danya Hernandez contributed to the reporting for this article.