Echoes of a 1970 Briefcase

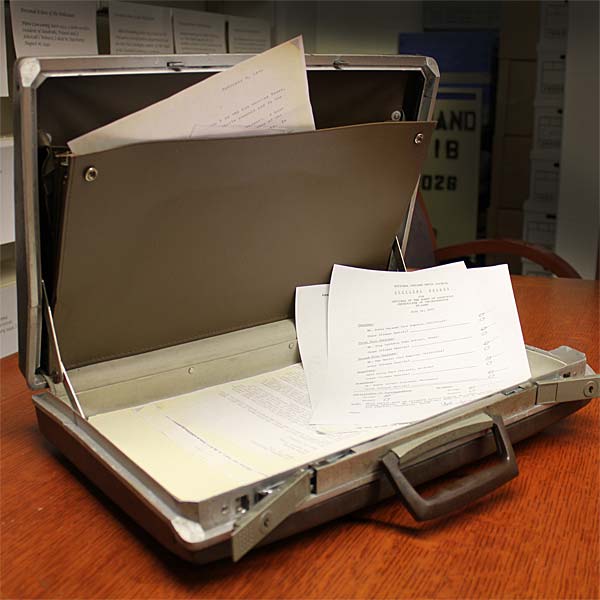

Opening a briefcase seems somewhat outdated in 2012. A corroded mark of rust came to life as I removed paper clips that seemed untouched since 1970. The smell of history matched the aged, brown, typewritten pages I held in the University of Southern California’s Doheny Library. It’s as if someone opened your laptop and read the documents and Internet tabs you left open on the morning of your death. This made me wonder how future historians will look into who we are today. When opening the briefcase I had walked into a moment in time that froze when Ruben Salazar was killed on August 29th, 1970.

My assignment for the Ruben Salazar Project asked that I peer into a pocket of the past in examining the documents found inside his briefcase. Salazar’s family donated an archive of his personal belongings to USC’s Doheny Library. We as a class worked to digitize a timeline of his life. The documents I read speak to the era in which Salazar lived and the direction he was taking in 1970. Moreover, when I opened the archive to my 2012 eyes Salazar’s loud voice thundered through a whirlwind of his unfinished conversations.

When he began at the Los Angeles Times in 1959, Salazar was concerned that he would be “typed only as a Mexican reporter,” according to an interview Dr. Mario Garcia had with former Times editor Bill Thomas. In fact, he lived a hyphenated Mexican-American lifestyle. After all, he lived a very “American” lifestyle. After joining the Times he married his wife Sally, who was Anglo, lived in an Anglo community in Orange County, and had friends who were Anglo writers from the Times. But Salazar’s place in history is far beyond the Mexican-American box and closer to a developing landscape of social justice.

Salazar’s identity was influenced in response to the changing times of the 1960’s as he became more confident with bringing who he was to the work he did as a reporter, although that fervor for empowering a hyphenated community wasn’t always explicit. While at the Times, Garcia explains that Salazar came to embrace his identity and role as an advocate for his community. Garcia frames Salazar’s growth within the changing dynamic at the Times. He argues that the paper rarely covered the Mexican-American community of Los Angeles until the 1968 blowouts when Chicano students walked out of local high schools to protest inferior education. Similarly, the Watts riots had brought the Black community of Los Angeles to the front page in 1965. The root of the actions that sparked the coverage lies in the brutal inequalities these communities faced.The killing of Salazar came as he was taking a break from covering an uprising against inequality and oppression of a marginalized community following the anti-Vietnam War Chicano Moratorium of 1970. As I looked at the contents of the briefcase, it occurred to me that on a fundamental level the inequality and discrimination that brought him to the moratorium took his life.

Advocating a Forgotten Community

On May 13, 1970, Salazar told Bob Navarro of KNXT-TV that he was advocating the Chicano community in the same way that the general media advocated the white power structure – “someone must advocate a community that has been forgotten” – Garcia writes in Border Correspondent. His 1970 briefcase reveals these stifled voices that he heard and wrote about.

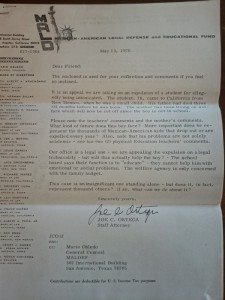

On the same day Joe C. Ortega, staff attorney for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), wrote to Salazar informing him of a student who was expelled for alleged intoxication. When I found this letter in the briefcase I was reminded of the role that others wanted him to play. The letter came with reports produced by teachers and other employees of the El Rancho Unified School District in Pico Rivera showing a flawed process of assessment and expulsion. The reports indicate the district treated the Latino student unfairly.

Ortega asked Salazar if this student “represents the thousands of Mexican American kids that drop out or are expelled every year?” This harsh disciplinary action that pushes out students of color concerned Salazar, and is still quite relevant. According to a 2010 Harvard Civil Rights Project report, students of color are more likely to be suspended or expelled from school and consequently form a greater percentage of our prison population. It’s been more than 40 years.

Unequal discipline in schools mirrored unequal enforcement of the law as well. Also in the briefcase I found a press release to Salazar from Congressman Edward R. Roybal. “Last night a tragic mistake by LAPD resulted in the death of 2 Mexican-Americans and the injury of a third,” Roybal said, arguing that the community’s faith and respect for law enforcement was shattered. Salazar underlined the lines portraying the police actions as a “systemic disregard for the civil rights of minority group citizens falling within their jurisdiction.” The congressman also mentioned that that five of the seven Mexican-American deaths in the East Los Angeles Sheriffs Sub Station in the past year year were attributed to “suicide” without adequate investigations by the Sheriffs Department.

Salazar’s attention was focused on these issues. His columns at the Times reflected frustrations with law enforcement and other issues affecting the Chicano community. He also presented these issues through Spanish-language television on KMEX, something the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) watched closely. Spurred by what I found in the briefcase I did additional research and found a police transcript of a KMEX news broadcast of March 11, 1970 covering protests at Roosevelt High School. The transcript found in the Times database summarized the news report with negative remarks by the police department, “the presentation of the news broadcast failed to be objective.” In the segment, students at Roosevelt were reported as saying, “the police department does not like the Mexican people.” LAPD monitored Salazar’s work and did not want him reporting on their actions. Garcia reports that Police Chief Ed Davis once called on Times editor Thomas, to fire Salazar and abolish his column. Salazar shook the establishment.

KMEX Gives Mexican-Americans a Voice

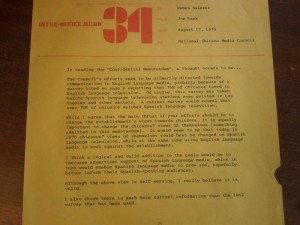

Among other documents in the briefcase I saw that Joe Rank, KMEX Vice-President, sent an inter-office memo on August 17, 1970, asking Salazar to not only “change the establishments views towards Chicanos,” but also “change Chicanos views of themselves”. He asked Salazar to act through both Spanish and English-language media, “Today in 1970 Chicanos view of themselves could best be changed on Spanish-language television, while at the same time using English-language media to work against the establishment.” In order to do this, he prompted Ruben to help with increasing advertiser support for KMEX.

Related to Rank’s memo and also found in Salazar’s briefcase was a piece Salazar typed describing the efforts of KMEX news and his hopes for its future direction. He writes KMEX is the “only station covering disturbances at Roosevelt High School and the killing by the LA police of two unarmed Mexican nationals”. He goes on to explain that the community news comes first, and that awareness begins at home in the “barrio” –which he underlines in his typewritten copy. Issues such as bilingual education, the Chicano movement, education, Chicano art and theater, and immigration were important to their constituency, Salazar wrote. KMEX was the only Spanish-language station broadcasting in Southern California at the time. Salazar expressed his vision for KMEX, writing that it could produce the first César Chavez documentary or a film on the differences between education in West Los Angeles and East Los Angeles.

Both of these documentaries would still be pertinent. Canana Productions announced in Spring 2012 that it had begun work on the feature film Chavez, featuring Michael Pena as César and Rosario Dawson as Dolores Huerta. Ruben Salazar had a similar vision 42 years ago. In his 1970 piece he writes, “What we need is money”. When I read this my thought was “Isn’t that what most Latino-based initiatives are asking for today–that advertisers recognize the market power of the Latino community in this country?”

Whether it’s Univision’s viral 2011 YouTube success – “The New American Reality” — telling that Latinos in the United States are the 15th largest consumer economy in the world or popular graphics on Facebook from Latinos Branding Power showing that Latinos have $1 trillion in buying power, the increased advertiser interest in reaching Latinos has expanded Spanish-language media in recent decades. In 1970, Salazar saw advertiser support of KMEX as a way of empowering the Spanish speaking community in itself. Ruben branded a new reality of power in this marginalized community 42 years ago.

Dolores Huerta Remembers Salazar

Hoping to find out more about Salazar’s interest in César Chavez, I caught up with early farmworker union leader Dolores Huerta at the White House Hispanic Community Action Summit in East Los Angeles on April 5, 2012. I asked her what she thought of Salazar proposing a César Chavez documentary in 1970. The question immediately reminded her of his abrupt death.

“Ruben Salazar was a person ahead of his time, he did have vision- unfortunately his vision was not able to come to fruition. My birthday is on April 29th and I just think August 29th, the word 29, always- I always confuse them. I still associate August 29 with Ruben Salazar and the day that they killed him.”

In his piece, Ruben Salazar mentioned having a relationship with the farmworkers movement and stressed KMEX’ s efforts to cover the issues affecting this community. Huerta commented on this:

“Ruben Salazar was actually a big supporter of the farmworkers. We had a march from Coachella to Calexico and Ruben Salazar accompanied us on that march. Right after that he wrote an article about the march and the farmworkers. Ted Kennedy was with us on that march -Jerry Brown as well.”

Huerta recalled Salazar’s early writing on the Bracero program and domestic farmworkers. He reported from Stockton in 1963 describing inhuman conditions among local farmworkers and providing a forum for organizers to compare the situation to a “mechanized slave market.” In reporting the story Salazar interviewed César Chavez. According to Mario Garcia, in 1965 Salazar wrote about the last Braceros to leave California – the same year he left California to be a foreign correspondent for the Times. But some Braceros didn’t leave forever. My family origins in this country began when my grandfather first arrived as a farmworker through the Bracero program and he later returned.

Closer to the end of the 1960’s, Salazar became a stronger advocate of his community, Huerta said. In our interview, she alluded to this as well.

“And prior to that time he really hadn’t done a lot of articles on the farmworkers…he had some sort of a conversion along the way . . . he did some things about the abuse of the police and farmworkers, before he hadn’t really done very much, it was like after he did those articles that they killed him…he wrote about police brutality, and it was after those articles that they killed him…and it’s a shame that he has not been vindicated.”

Sal Castro Remembers Salazar

A few days prior to my meeting with Huerta, I spoke to one of the primary agents of the 1968 High School Blowouts in Los Angeles, Sal Castro. Castro was a teacher who supported students in their expressions for bilingual education as early as 1963. Castro said he helped students start the Tortilla Movement at Belmont High School where students ran for political office in Spanish and English. The students were suspended for speaking in Spanish, so he sought to defend them.

Salazar was particularly interested in these issues with bilingual education, so he interviewed Castro for a six-part 1963 Times series called “Spanish Speaking Angelenos,” which would bring him recognition and a stronger connection with issues affecting the Mexican-American community of Los Angeles. According to Garcia, Salazar wrote, “Until Mexican-Americans could be proud of their own identity, little social progress could be achieved.” This was something I believe Salazar would also come to terms with over the course of his career.

Huerta mentioned that there was “some sort of conversion along the way” and Castro echoed that feeling in his interview. Sal Castro is one of few public figures alive today who knew and was covered by Salazar before and after Salazar’s work as a foreign correspondent (1965-1968). I asked Castro about the differences he saw in Salazar before and after his work as a foreign correspondent.

“He was a writer that wasn’t as farsighted and as concerned about the community, – – well he was always concerned with his community when he came back from Texas -of course- he wouldn’t have written otherwise. But you still had to keep your job at the Times. This was 1963, you really don’t rock the establishment that much, otherwise you might be out of a job. He was much more hard hitting when he came back, and his thoughts and his thinking were much more aware of what was going on…”

Castro believed Salazar’s experiences as a correspondent made him more “aware” and “comfortable” with who he was, thus enabling him to advocate for his community. Castro explained the October 1968 Tlatelolco massacre of students by the Mexican military in Mexico City and how he perceived covering this story had affected Salazar. Framing this in the context of the East Los Angeles walkouts of March 1968 and the Mexican government’s efforts to polish its image before the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City by literally shooting down public dissent, Castro said this “really angered Salazar, and gave him additional depth.”

“I could see that his experience had deeply affected him – like I said the first words out of his mouth- Manito como a cambiado todo…When he returned, he saw that they weren’t going to take it anymore. He was much more able to connect to the community,” said Castro, recalling their first conversation after Salazar returned from Mexico.

Salazar’s Columns for the Times

The typewritten copy Salazar filed for his 1970 Times columns that I found in his briefcase are a testament to this growing fervor and development in Salazar’s vision. One of his most well known columns in the Times titled “What is a Chicano?” examines the identity of the people behind the movement for social justice and explains the term and identity of “Chicano.”

Salazar found value in what it meant to be a Chicano. On the third page of the article he writes that Mexican-Americans ask why they should identify as Chicano rather than simply American – to which he provides an answer. “Chicanos are trying to explain why not. Mexican-Americans, though indigenous to the Southwest, are on the lowest rung scholastically, economically, socially, and politically. Chicanos feel cheated. They want to effect change. Now.”

The issues sound familiar, but the Chicano movement seems to be a vague term with a weird and different face more than 40 years later. Sal Castro remembers this article clearly.

“He wrote a hell of an article on “What is a Chicano” -an aware Mexican who is proud of his heritage – becomes a Chicano. There was a lot of talk of Chicanos being a bad word, but all it was was an attempt… like the Black community. First they were Colored, then they became Negro, then Black, now they are African American. An aware Negro is a Black. He is proud of his roots and his heritage. That was Malcolm X’s idea of being Black. The idea of the word Chicano to Ruben was I think that this guy was an aware Mexican wherever the hell he was born, and proud of his roots, his heritage, and comfortable in his own skin – that’s how one became Chicano.”

It seems to me that when Ruben Salazar came back to a rising movement for social justice, that he too learned to identify with, he was met with the need to both describe and give voice to a disenfranchised people. Salazar’s evolving identity and newsroom career met the growing tide of grassroots mobilization. Castro said:

“I think that was the crux of when he came back from Mexico, ‘I’m becoming much more comfortable with myself knowing that I’m working with the majority community but that doesn’t mean I have to give in’.”

Salazar in Demand

Salazar was in high demand given his rare presence as a journalist covering Chicano stories in an era when very few Latinos worked in English-language media and even fewer worked in both English and Spanish. In the briefcase a February 20, 1970 letter from Robert Campbell, Executive Director for the Race Relations Information Center, reminded Salazar to follow up with an article he committed to writing on the student movement among Mexican-Americans.

These kinds of commitments also affected his personal life and took time away from his family. His daughter Lisa Salazar Johnson remembers her father coming home at around 8 p.m. every night after she had dinner. “It was a big deal if we took a trip to Sea World, because he was so busy.”

Salazar’s Commitment to Progress Through Education

The extensive hours he spent covering issues reflect his personal commitment in fighting for progress. His daughter Lisa remembers “he was so big on education.” He felt education was essential to resolving issues for the Chicano community in 1970.

This is still an issue today. Compared to all major ethnic groups in the country, Latinos have the lowest educational achievement. These gaps are demonstrated in Patricia Gandara’s The Latino Education Crisis published by Harvard University, and a 2006 article by Tara Yosso and Daniel Solorzano called Leaks in the Chicana/o Educational Pipeline.

Salazar’s last column ran under the headline “The Mexican-Americans NEDA Much Better School System” on August 28, 1970. He writes, “The following has been said and written about many times, but it has yet to effectively, penetrate the minds of our national leaders: The Mexican-American has the lowest educational level, below either Black or Anglo; the highest dropout rate; and the highest illiteracy rate.” Substitute the word Mexican-American for Latino, and this statement would stand today. Salazar fought for issues we have yet to resolve now, more than 40 years later.

A day after this piece on education was published in the Times, Ruben Salazar was killed following the Chicano Moratorium. Neither his vision nor the issues he confronted with his writing came to a close in 1970. The conversations I discovered in his briefcase are still un-ended today.

[…] by nine undergraduate and graduate USC Annenberg students. They are: Elaine Baran, Melissa Caskey, Juan Espinoza, Regina Graham, Gustavo Gutierrez, Grace Jang, Elena Kadvany, Bianca Ojeda and Frances […]

[…] students were: Elaine Baran, Melissa Caskey, Juan Espinoza, Regina Graham, Gustavo Gutierrez, Grace Jang, Elena Kadvany, Bianca Ojeda and Frances […]